A Brief History of Bonk, Part 1 (Bonk Through the Ages)

An almost comprehensive overview of blunt weapons from Pre-History through the Iron Age

Among man's first attempts to exceed his own bodily limitations, clubs have seemingly always existed, perhaps long before they were even conceptualized. Though quickly and easily overshadowed by other forms of weaponry in many historical circumstances, they have never dropped out of existence entirely. This is due primarily to material abundance, ease of construction, ease and flexibility of use, great variability in design, and man's inability to by-pass a cool looking stick in the forest without swinging it around a few times.

Our journey begins of course well beyond the reaches of recorded history in the stone age (neolithic, mesolithic, paleolithic eras), or as it is affectionately known by enthusiasts, “The Golden Age of Bonk”, where the very earliest clubs were hardly constructed or fashioned at all, but were simply objects that happened to have a natural structure suitable for striking, like femurs:

Or jaws:

However, it is the wooden club, as a central figure, that has been carried forth through history. At its absolute simplest, the wooden club is a limb or trunk of a tree (preferably the hardest wood available), narrowed at one end to be gripped by the hand, and left larger at the opposite end for striking.

Historians theorize that this form of club, one that most certainly preceeds the limits of archeological discovery, could have been the first implement fashioned specifically for combat against other humans, as opposed to stone/flint/bone spears, arrowheads and knives, which were first and foremost tools for hunting/utility.

Wooden archaeological finds from antiquity can be difficult to come by (as with leather) since organic materials are prone to decay. However, given the proper environment for preservation, wooden items can survive, and one such example of an ancient Neolithic club is known as the Thames beater:

UK scientists found they could replicate skull fracture patterns found on Neolithic humans using reconstructions of the Thames beater, almost certainly proving that wooden clubs, even in this simplest form, were a popular and deadly instrument of war.

One of the first technological variations of the club to arise was the ball end, which has examples across the world. Instead of being simply a carved straight branch or trunk, a ball club had a head fashioned from the juncture point where the branch or trunk met roots or another limb, providing a denser, more durable and concentrated striking surface:

Of course, alternative steps in the neolithic evolution of the club were to replace the striking head altogether, with a different material such as stone, attached by sinew, or embedded in pieces along the length of the club.

From this point forward, as wide as there are variations in geography and culture, so are the variations in club design and material construction:

In the South Pacific (micronesia, polynesia) stone, ivory, bone, and even shark teeth were used in addition to very hard wood fashioned into points, protrusions and ridges:

Similar designs were used by the aboriginal populations of North America:

The Aztecs and other tribes in volcanic environments added shards of obsidian to their war clubs:

African examples:

As you may by now have guessed, the best extant examples of war clubs from stone age materials come from areas of the world who had little to no metallurgy until the modern era, but access to very hard woods, and so have actually been constructed relatively recently. The wealth of examples found in Africa, the South Pacific, and North and South America are our greatest windows into the Golden Era of Bonk. In Europe and Asia, metallurgy has been around for thousands of years, thus relegating the club to a more background role in favour of spears, axes and swords made from bronze or iron. This is not to say that blunt weapons were unknown in the bronze age - far from it.

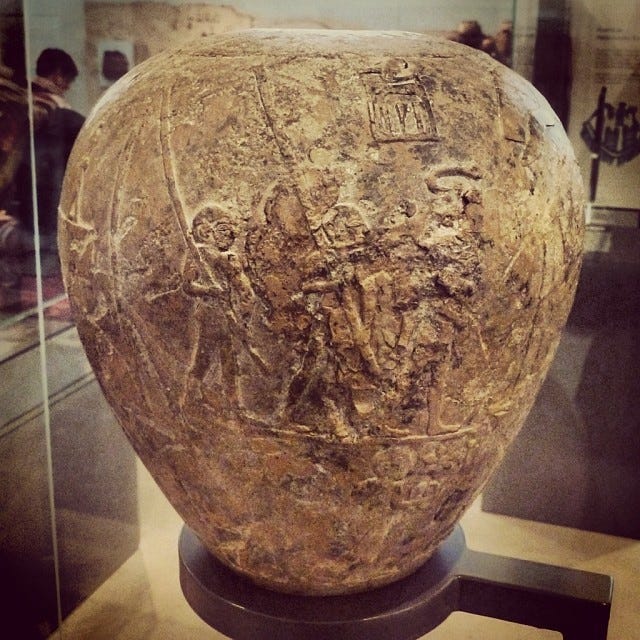

In the transitional period from the late Neolithic into the early Bronze age, (Approx. 4000 BC to 2500 BC) Egyptian, Sumerian, and Akkadian warriors carried the stone-headed mace as one of their primary weapons.

These cultures are the oldest examples we have of a club/ blunt weapon being a primary armament of an organized military force. It is also in Sumeria that we find the first record of a legendary mace, that being Sharur, “smasher of thousands", weapon of the god Ninurta, mentioned in Sumerian epic poetry.

The stone mace remained in military use throughout the bronze age, although becoming gradually eclipsed, having to share the stage with a wide variety of bladed weaponas. However, blunt weapons were produced in bronze as well and we have examples of those mace heads from middle/near eastern/Aegean cultures all throughout the bronze age, until 1200 BC and even later:

Though its combat role was gradually reduced, the mace/club continued to hold significant ceremonial and symbolic meaning to the peoples of the Bronze age nonetheless, and it seemed to have just as much importance for the Assyrians and Babylonians as it did for the Sumerians. It is quite common throughout these middle-eastern cultures for Gods and Kings to be depicted holding some sort of blunt weapon, which seems to indicate that the weapon had enduring meaning as a representation of power, authority, and masculinity, and was perhaps the beginning of the royal tradition of the mace which will be discussed later.

Examples of ornately engraved mace-heads also survive, which were likely ceremonial/status-symbols/votive offerings:

This reverence for the mace/club extended to the neighbouring Indian sub-continent as well, where representations of the Hindu gods beginning in the Vedic period often feature such weapons in similar roles of prominence.

In the Agni Purana, an Indian martial arts manual from this period, instruction is given on the use of the Gada (mace) in combat. Indeed, Gada training holds a central place in Indian (and Persian/Iranian) martial tradition, being carried forth into modern times as an exercise discipline, and its origins were at least as old as the bronze age, though likely extending long before that. The looser fighting formations used in Indian warfare helped keep the mace relevant for a longer period of history as opposed to the Hellenic and post-Hellenic west. Gadas come in many materials, depending on their purpose and region of origin, with examples in stone, wood, and metal likely following a similar pathway of material evolution to maces in the Mesopotamia.

Among the Celts and other European tribes of the bronze age, blunt weapons, though certainly extant, seem to have been less commonly used than in the Middle East, India, and even the Aegean. In his work, “A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland", P.W. Joyce has this to say:

The Mace—The club or mace—known by two names—matan and lorg—though pretty often mentioned, does not appear to have been very generally used. In the Tales, a giant or an unusually strong and mighty champion, is sometimes represented as armed with a mace. There can be no doubt that the mace was used: for in the National Museum in Dublin there are several specimens of bronze mace-heads with projecting spikes. One of them is here represented, which, fixed firmly on the top of a strong lorg or handle, and wielded by a powerful arm, must have been a formidable weapon.

Entering the Iron Age, blunt weapons begin to fall even further out of regular use, with examples being few and far between. Indeed, in Greco-Roman (and Carthaginian) armies after 700 BC, blunt weapons are almost unheard of. It seems safe to say that by this point in history, a warrior wielding a mace or club, especially with two hands, was a largely vestigial occurrence in Europe and the Middle-East, probably viewed as a by-gone relic of the previous age. None the less, reference to their existence can still be found, for example, in Homer:

“On their side stood forth Ereuthalion as champion, a godlike man, bearing upon his shoulders the armour of king Areithous, goodly Areithous that men and fair-girdled women were wont to call the mace-man, [140] for that he fought not with bow or long spear, but with a mace of iron” - the Illiad

This passage tells us quite a bit. Firstly, it provides us with clear evidence of a blunt weapon used in early Iron/Late bronze age Mediterranean combat. Secondly, it seems to imply that this was an exception to the norm of armament. Lastly, that the man wielding it was likely more physically powerful than the average soldier.

There is passing reference to Iron Age use of a thonged wooden club called an Aklys by an Italic tribe known as the Osci, and reports from Greek historians of spiked clubs in rare use among the Achaemenid Persians, but battlefield examples are highly limited compared to the Bronze age. However, another exception may be found in the Germanic tribes of the Iron age and later, who have a number of attestations and depictions that declare their use of wooden clubs, including this image from Trajan's column:

As was mentioned earlier in the article, ancient wooden archaeological finds are very rare, but still happen enough to support the theory that wooden clubs are a weapon which, throughout history, never completely disappear. Below is one such rare find, a pair of clubs from a battlefield in Tollense Valley, Germany, around 1250 BC:

If it was only rarely found on the battlefield in the Iron Age/classical era, the mace/club certainly still retained its ancient status as a symbol of power and masculinity. The Roman centurion carried a thin wooden club or staff called a Vitis, which was a symbol of rank, as well as a tool used to direct drills, and even inflict punishment upon slacking or disobedient soldiers.

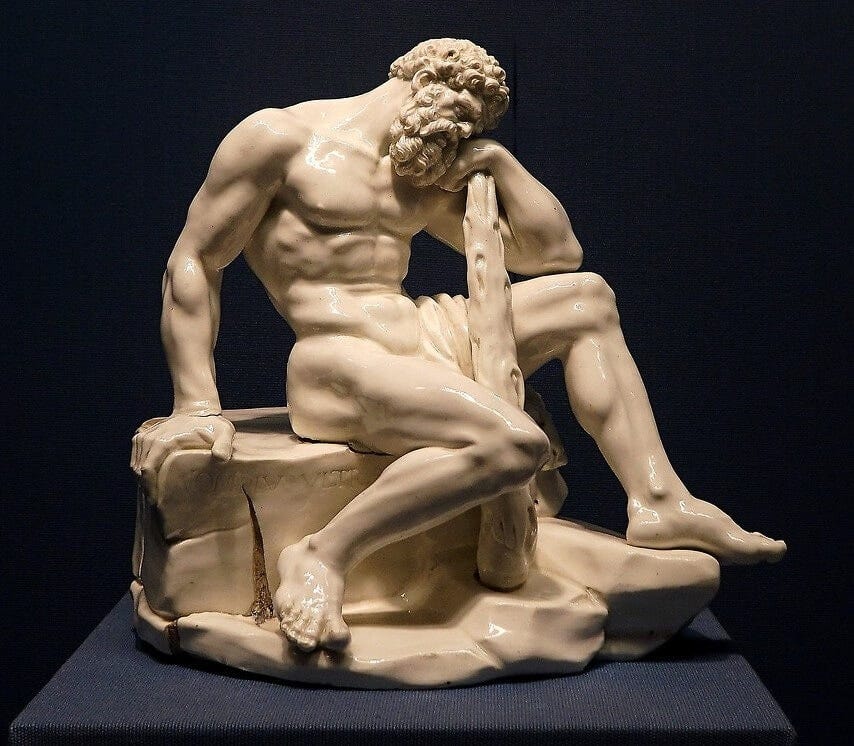

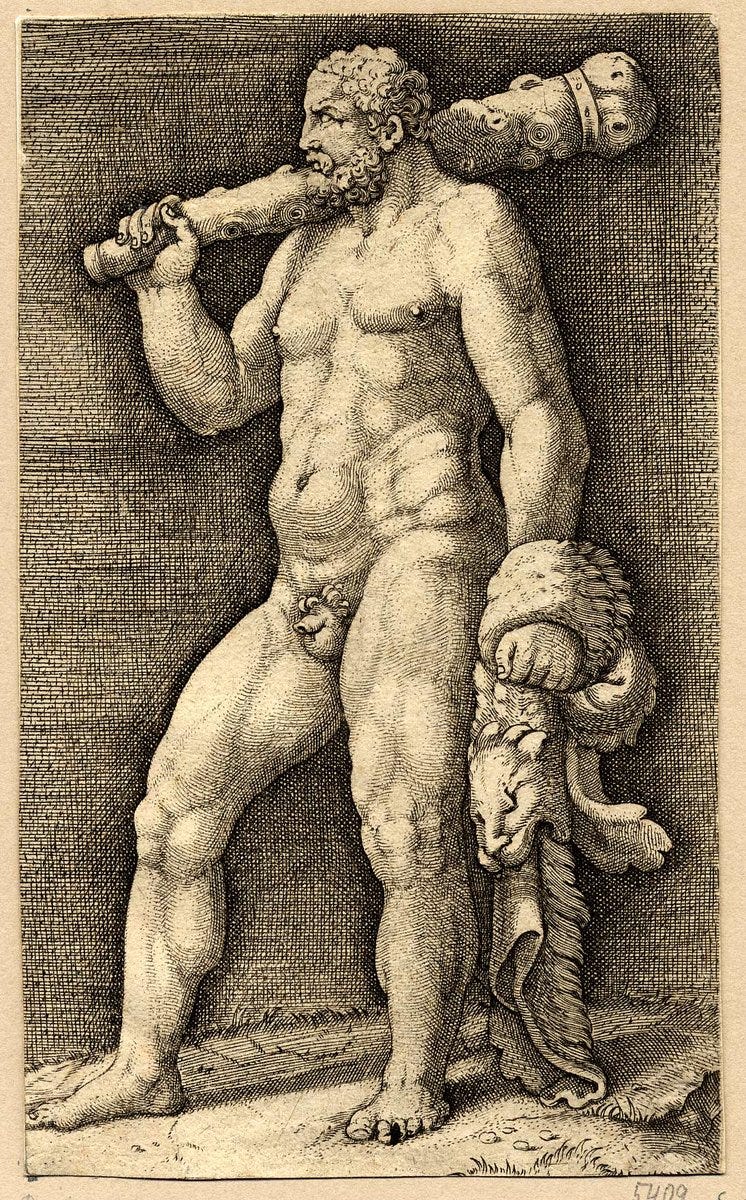

The mythical Hercules/Heracles, whose legend permeated Greco-Roman culture and the west in general, is perhaps the most famous club-wielder of all time:

A demi-god with a primitive aspect celebrated for incredibly bodily strength, the roots of Hercules are probably as ancient as the club he wields. The club of Hercules was so popular amongst the Romans, that it was commonly worn as an amulet, and found all across the empire, being also adopted by the Germanic tribes for whom Hercules may have become intertwined with their god Donar, himself a club/hammer/axe wielder.

Another instance of the symbolism of the club in Roman society was the scepter held by Emperors, likely related to the maces held by the bronze age Mesopotamian/Indo-Iranian kings, the Roman scepter would itself endure in western culture into the present day.

Now we must pause, at this low-tide in the ocean of bonk. At the time of the man above's death, we have only just barely entered the first Millenium AD, and already the club is incredibly old beyond measure. It that sense, it is one of the rare items to be already thoroughly antiquated in the period we call antiquity; the ancient history of the ancients. In another sense of itself, it is a timeless and enduring symbol of strength and power. At the start of Indo-European history, in Mesopotamia and Egypt, it was stone and wood, standard issue for the fighting man, only to become one bronze tool among many, and then just an infrequent occurrence, when necessitated by an opponents armour. By the start of the Iron Age, the men who wielded great clubs were already half-passing into legend; a few of the strongest and largest warriors on the field who strode forth from the misty shrouded past as defiant testaments to primal power. The story of the club is not finished, but we will rest here and contemplate these giants.

An extremely practical, utilitarian and aesthetic article! Could prove vital for the times we live in! The History of Bonk should be considered essential for all colleges and universities! Definitely part of our Proud Survival Heritage!

BONK